Frequently Asked Questions

- I haven’t committed any crimes. Why should I care about expungement?

- Does expungement put society at risk by hiding the truth about a person?

- Shouldn’t we just give people the criminal records and let them decide if the criminal record is relevant?

- If a person committed the crime, shouldn’t they have to deal with the consequences?

- Aren’t there other laws in PA that accomplish the same goal as SB 391?

I haven’t committed any crimes. Why should I care about expungement?

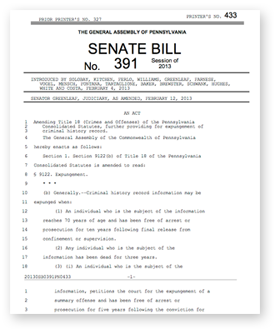

Allowing former offenders who have been rehabilitated to earn a second-chance saves taxpayers money, makes Pennsylvania safer, and creates a system where people continue to pay what they owe due to a conviction, but nothing beyond. Senator Solobay’s proposed bill, SB 391, is designed to modernize Pennsylvania’s approach to the long-term reporting of minor criminal records, amending Title 18 to allow individuals who have served their punishment and remained free of arrest or prosecution for seven to ten years to request to have their record expunged.

Does expungement put society at risk by hiding the truth about a person?

No. Senator Solobay’s Expungement bill, SB 391, deliberately limits the availability of expungement to low-level offenders, such as those who have only committed 2nd or 3rd degree misdemeanors. The law further requires definitive proof that the applicant has gone at least seven years without an arrest or conviction. Habitual offenders with many offenses may not apply. Felonies, first degree misdemeanors, and offenses requiring sex offender registration are never eligible. Finally, the prosecution may file an objection to expungement petitions, in which case the judge has discretion in granting or denying the request.

Shouldn’t we just give people the criminal records and let them decide if the criminal record is relevant?

First, SB 391, is about stopping the medieval practice of having government label low-level offenders as criminals for life. As Senator Solobay stated in his memo accompanying SB 391, “[a] low-level misdemeanor in a person’s past can often serve as a continual barrier when seeking work, long after they have completed their sentence.” As it stands, low-level offenses will haunt a person for life, making it impossible for them to find employment, housing, and education. The proposal benefits all Pennsylvanians “by countering high rates of recidivism, relieving an overburdened pardon system, and providing [opportunities] for ex-offenders to join our workforce.”

Second, SB 391 only affects the type of records that no rational person would use to discriminate against another person. SB 391, like many laws, is designed to stop irrational discrimination that hurts the victim and all of society.

If a person committed the crime, shouldn’t they have to deal with the consequences?

Pennsylvania’s criminal statutes are well-versed in intentionally punishing offenses, particularly in setting sentences that reflect the nature of the offense. In contrast, SB 391 is about fixing unintended consequences of crime that have unjustly developed. Long after serving their sentences, many people who commit misdemeanor offenses face a lifetime of discrimination for housing and employment. These consequences are not only grossly unjust, but increase our crime rates by making it impossible for rehabilitated former offenders to re-join our society. Furthermore, these types of collateral consequence in no way deter criminal violations. For example, a person who is contemplating stealing a hammer at a hardware store or who gets into a scuffle at a sporting event likely expects a minor jail term or fine when considering whether to commit a crime, but finding housing or providing food for their family in 15 years are not consequences that a potential offender considers. Keeping former offenders unemployed and stuck in bad neighborhoods only serves to unjustly increase the chances that they will reoffend.

Leave a Reply